Keeping cool in a warming world is not a “luxury” for the rich; it can be a matter of life or death

The heatwaves, currently experienced in Europe, should be a wake-up call to stop ignoring summer domestic energy poverty.

Domestic energy poverty, and its implications on health and well-being of the occupants, has historically been considered in Europe a winter issue. However, excessive temperatures reached in summer, especially during heatwaves like those we are currently experiencing, are also harmful to peoples’ health, and can lead to the death of the most vulnerable ones. During the record-breaking heatwave in 2003, one should not forget that excess deaths were above 30,000 in Europe due to hot temperatures in buildings including in hospitals and care facilities.

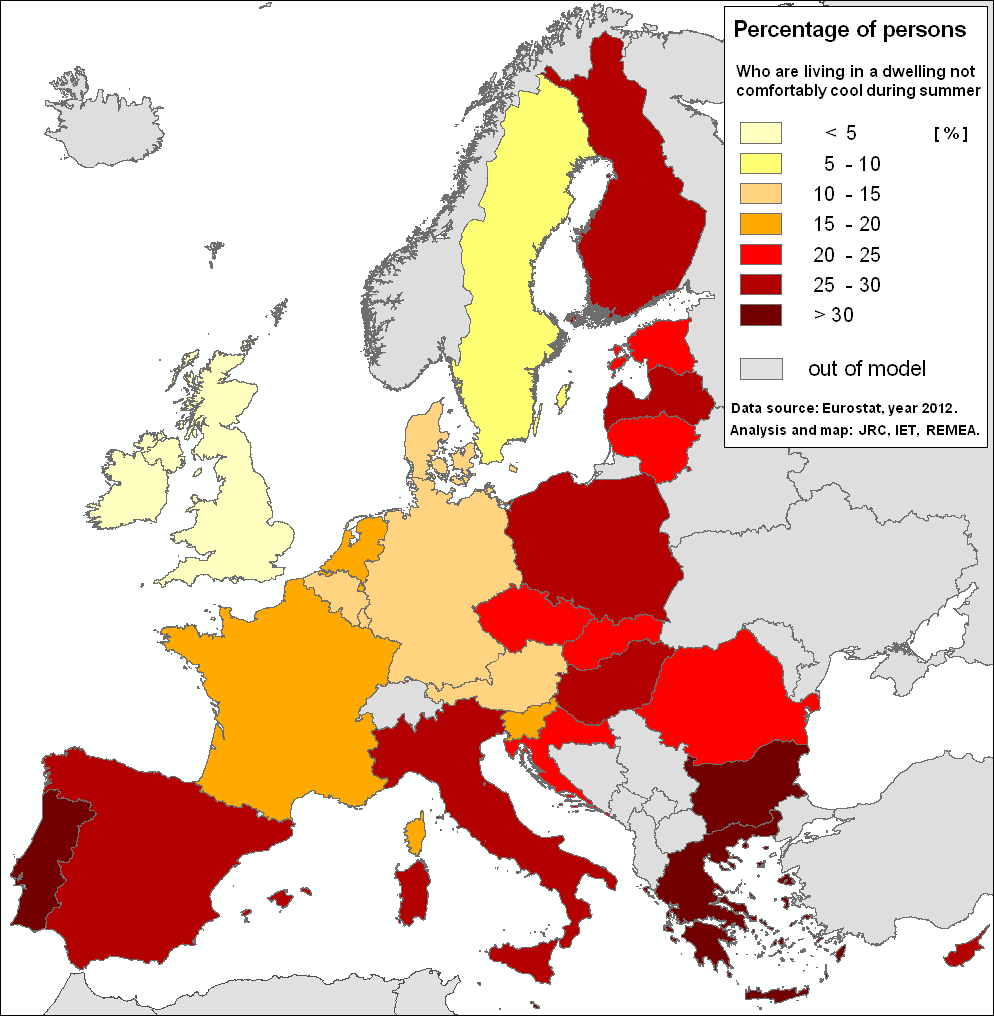

The lack of interest in overheated dwellings and their impact on human health could be explained by the scarcity of data to support clear policy action. Since 2005 EUROSTAT provides on a yearly basis, the percentage of the population who is not able to keep their homes adequately warm in winter. Winter statistics and political actions to protect the more vulnerable citizens are becoming a standard in the policy realm of most European governments. Unfortunately, we have little information regarding the percentage of the population living in homes who are not comfortably cooled in summer or who lack the means to keep their inhabitant healthy in high summer heat. In fact, summer information is provided only for 2012 in EUROSTAT (see map below).

Source: Energy Renovation: The Trump Card for the New Start of Europe, JRC, 2015

The way statistics related to summer domestic energy poverty are considered seems highly problematic. Measurements of winter domestic energy poverty are considered among the main indicators to monitor domestic energy poverty in the EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV). While measurements of summer domestic energy poverty are considered as secondary indicators in EPOV. This hierarchization of domestic energy poverty indicators participates in undermining potential actions on summer domestic energy poverty in policy making. Similarly, excess mortality data are available only for winter time in the EU Building Stock Observatory, and very few Member States gather data on excess summer deaths.

Policy makers, especially in Southern and South-Eastern European countries, should be worried about the ever-growing evidence regarding the impact of global warming on increasing the frequency of extreme heat-related events and their effects on health and well-being of vulnerable citizens. In some countries, the shares of the population facing summer related domestic energy poverty are already extremely high and alarming (see map below). The current policy response to heatwaves is, mainly, limited to the Heat-Health-Warning Alerts which are designed to ensure that emergency responses are more efficient and better coordinated than they were in 2003. Their objective is to limit related health risks and fatalities during heatwaves.

Although emergency response measures may be effective in the short-term, and limit the consequences of summer domestic energy poverty, they seem inadequate given the expected frequency and severity of heatwaves. For the longer-term strategy, policies should also consider the causes of overheated dwellings. Unfortunately, current building regulations are only looking at the winter side of the problem. They, mainly, require to super-insulate buildings and to improve their airtightness. Instead, building regulations should begin to seriously consider overcoming the overheating risks by requiring an increase of buildings’ thermal mass, the implementation of night-time ventilation solutions and the installation of solar shadings as well as cooling systems to keep indoor temperatures at an acceptable level for the inhabitants

Keeping buildings cool in summer is not a “luxury” – it is a necessity, and literally a question of life or death. Taking action will not necessarily lead to an increase of greenhouse gas emissions if solar technologies are required in building regulations and renovation strategies. Moreover, cooling systems will not increase the energy bill of low-income households if powered with PV. Solar technologies could offer comfortable homes at almost zero cost and – if well-designed – could also offer warmth in winter – hence alleviating domestic energy poverty both in summer and winter times.

Summer will not just fade away when most Europeans will be back to work and kids back to school. Hot temperatures may last longer into the fall months. Current heatwaves should sound alarms all over Europe and question the status-quo in building regulations about overheating risks. Academia and NGOs must join forces and help policy-makers in the design of measures to protect from this new danger the most fragile and often isolated populations. Importantly, industry must, urgently, put in the market cost-effective and innovative solutions to alleviate energy poverty both in summer and winter times.

Rendez-vous next summer. (and remember your air-conditioned office!)

This column was published for the first time on August 6, 2018 on Euractiv